We need to talk about Glinda. We need to talk about complicity. We need to talk about how Wicked: For Good gives us a story that I’m not entirely sure was worth telling in the way it chose to tell it.

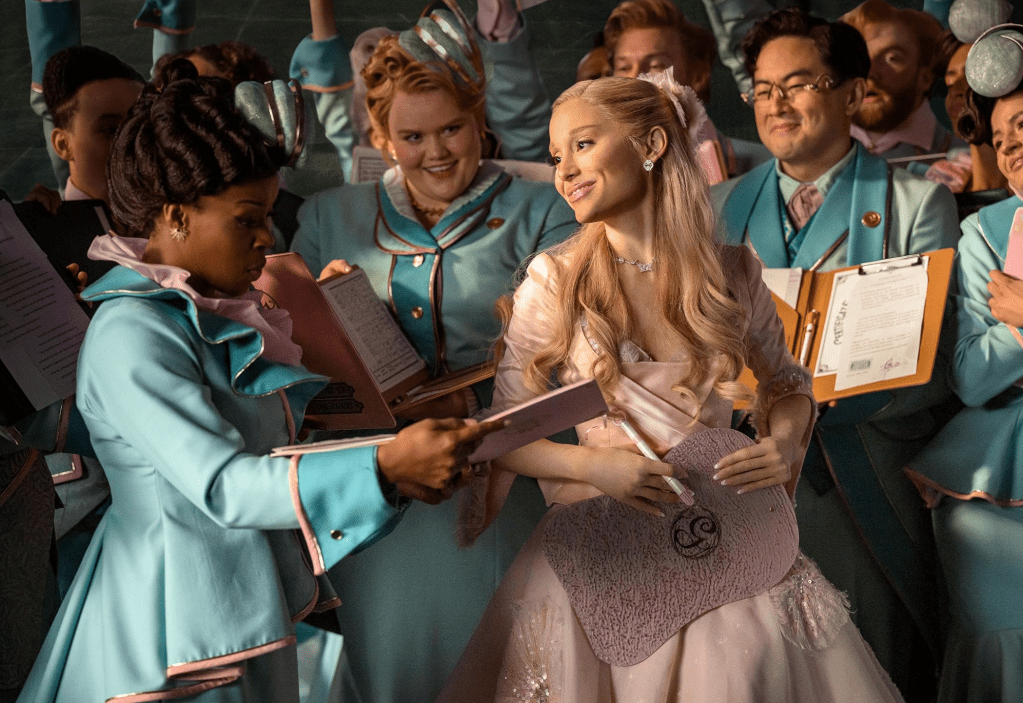

Let me start by saying this: Wicked: For Good is technically accomplished, gorgeously shot, and features moments of genuine emotional power. Cynthia Erivo remains a force of nature, and Ariana Grande does some of her finest work in the film’s quieter moments. Jon M. Chu’s direction is assured, the production values are impeccable, and there are sequences that took my breath away. This is a competently made film by people who clearly care about the source material.

But caring about something and understanding what it’s actually saying are two different things, and For Good stumbles in ways that leave me deeply conflicted about what story we’re ultimately being asked to accept.

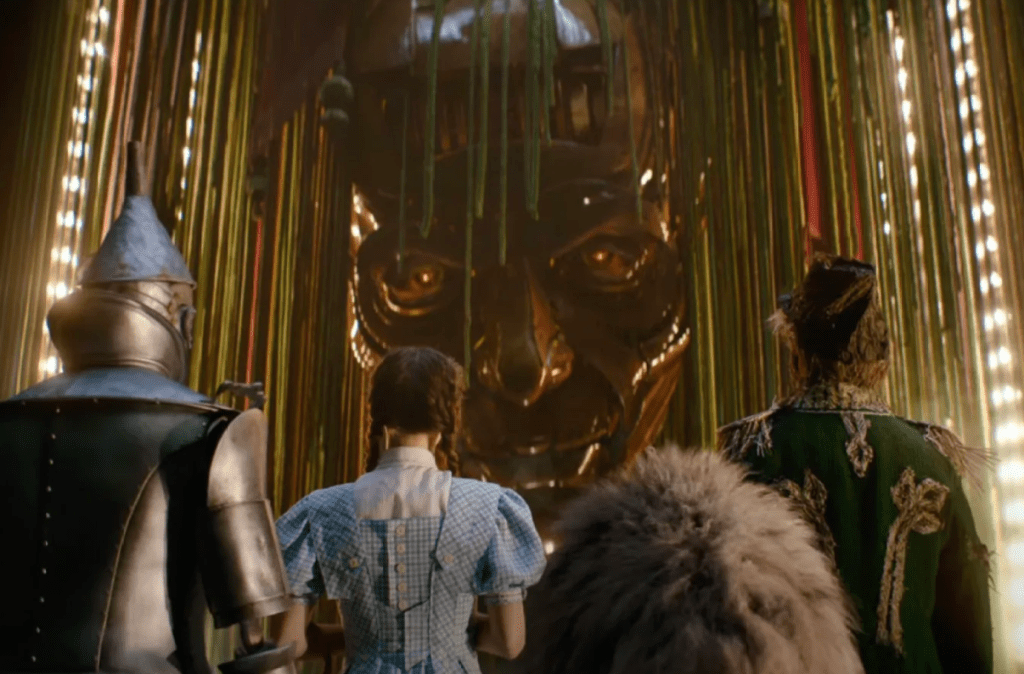

Part 1 ended with Elphaba flying away, choosing truth over belonging, becoming a fugitive to fight injustice. It was triumphant and heartbreaking in equal measure. Part 2 picks up with Elphaba living in hiding, still trying to rescue Animals and expose the Wizard’s lies, while Glinda has fully embraced her role as Glinda the Good—bubble transportation, sparkly gowns, and all. She’s become the face of the Wizard’s regime, traveling Oz to reassure people that everything is fine, that Elphaba is the real threat, that if everyone just trusts the system, all will be well.

And here’s where my issues begin: the film seems to want me to view Glinda as someone caught in an impossible situation, someone struggling with the choices she’s made. But what I see is someone who actively, repeatedly, consciously chooses power and comfort over doing what’s right. And the film’s insistence on redeeming her rings hollow when we see exactly what she’s complicit in.

Let’s be clear about what Glinda does in this film. She stands beside the Wizard as he consolidates authoritarian control. She uses her popularity to legitimize his regime. She watches Animals be persecuted and does nothing. She participates in propaganda campaigns against Elphaba, her best friend, knowing that Elphaba is telling the truth. She prepares to marry Fiyero in a lavish ceremony designed to distract the populace while oppression continues unchecked. At every single turn, when Glinda is given a choice between doing the right thing and maintaining her position, she chooses herself.

The film gives us several scenes of Glinda looking troubled, of her singing about being in a bubble (the new song “The Girl in the Bubble”), of her clearly feeling bad about what’s happening. But feeling bad while continuing to benefit from and actively participate in an oppressive system is not growth. It’s the bare minimum of having a conscience while refusing to act on it.

And then—and this is where I really need to talk about the change from the stage musical—the film gives Glinda magic powers.

In the original stage show, Glinda cannot do magic. It’s a crucial element of her character. Her “powers” are all technological tricks provided by the Wizard, and her bubble is just a machine. This serves as a perfect metaphor: Glinda isn’t actually special or powerful in the way Elphaba is. Her power comes from her privilege, her willingness to play along, her ability to make people like her. She’s a figurehead, a face, a distraction. That’s the point.

But the movie changes this. In the film’s final act, after Elphaba gives Glinda the Grimmerie, the magical book opens for Glinda, suggesting she now has real magical abilities. Director Jon M. Chu and Ariana Grande have defended this choice, saying Glinda “earned” her magic through trauma and hardship, that her suffering awakened powers she always had but couldn’t access.

I… have problems with this.

First, it fundamentally misunderstands what makes Glinda’s character arc interesting. Glinda doesn’t need magic to be powerful or to do good. Her actual power—her popularity, her influence, her ability to sway public opinion—is already immense. Giving her literal magic powers undercuts the entire point of her character, which is that she’s someone who has all the tools necessary to fight injustice but chooses not to use them until it’s too late.

Second, the idea that Glinda “earns” magic through trauma is… deeply uncomfortable when you consider that Elphaba has been traumatized her entire life. Elphaba was rejected by her father from birth, ostracized for her skin color, blamed for her sister’s disability, and systematically othered by everyone around her. Her magic didn’t come from “earning” it through suffering—she was born with it because of who her parents are. Creating a narrative where Glinda gets magic as a reward for finally experiencing hardship feels like it’s centering the privileged person’s journey toward enlightenment rather than acknowledging that some people never had the luxury of ignorance.

Third, and most importantly: Glinda doesn’t actually do anything meaningful with this supposed power until after Elphaba and Fiyero are gone. She doesn’t use it to fight the Wizard or Morrible while they’re still a threat. She doesn’t use it to help Elphaba when Elphaba needs her most. She stays in Oz, accepts Elphaba’s “death” as necessary, and only then does she finally banish the Wizard and imprison Morrible. Only when her best friend and the man they both loved are dead (as far as she knows) does Glinda finally do the right thing.

Let’s talk about the ending, because this is where everything comes to a head. The film reveals that Elphaba faked her own death so she and Fiyero could escape Oz together. Glinda knows the truth—that Elphaba was never the Wicked Witch—but Glinda chooses to let everyone believe Elphaba was just as wicked as they thought. She takes credit for “dealing with” the Wicked Witch and uses that credibility to finally reform Oz.

Until reading interviews with Jon M. Chu and Ariana Grande, I genuinely interpreted the final scene—where we see the book opening as Elphaba begins her new life—as Elphaba’s way of letting Glinda know she made it out, a secret signal between friends. It felt like a moment of connection, of Elphaba reaching across the distance to say “I’m okay. I’m free. And I forgive you.” That reading gave the ending grace and hope.

But Chu has confirmed that it’s actually meant to show Glinda accessing her newly awakened powers. And Grande talks about how Glinda finally becomes truly good, how this is her triumphant moment of transformation. And I’m left wondering: are we really supposed to celebrate this? Are we really meant to think Glinda is a hero because she waited until everyone she loved was dead or gone to finally take a stand?

Because here’s what I see: a woman who had every opportunity to do the right thing and didn’t. A woman who chose proximity to power over solidarity with the oppressed. A woman who watched her best friend be vilified, hunted, and murdered, and did nothing to stop it. A woman who actively participated in propaganda campaigns against that friend. A woman who only found her courage after there were no more personal costs to being brave.

And we’re supposed to think she’s good now? That she’s redeemed?

This is where the film’s politics become muddled to the point of incoherence. Wicked is clearly trying to say something about how we define good and evil, about how propaganda shapes public perception, about how systems of oppression persist because good people do nothing. The first film did this beautifully. But the second film seems to argue that doing nothing, doing active harm even, is forgivable if you feel bad about it and eventually, when it’s safe, do something good.

I think about the children watching this movie. I think about the message it sends: that it’s okay to go along with injustice as long as you’re uncomfortable about it. That personal safety and comfort are understandable reasons to abandon your principles. That redemption is available even if you only act after all the real danger has passed. That the privileged person’s journey toward enlightenment is just as important, just as worthy of celebration, as the marginalized person’s fight for survival.

And I wonder: is that really the story we need right now?

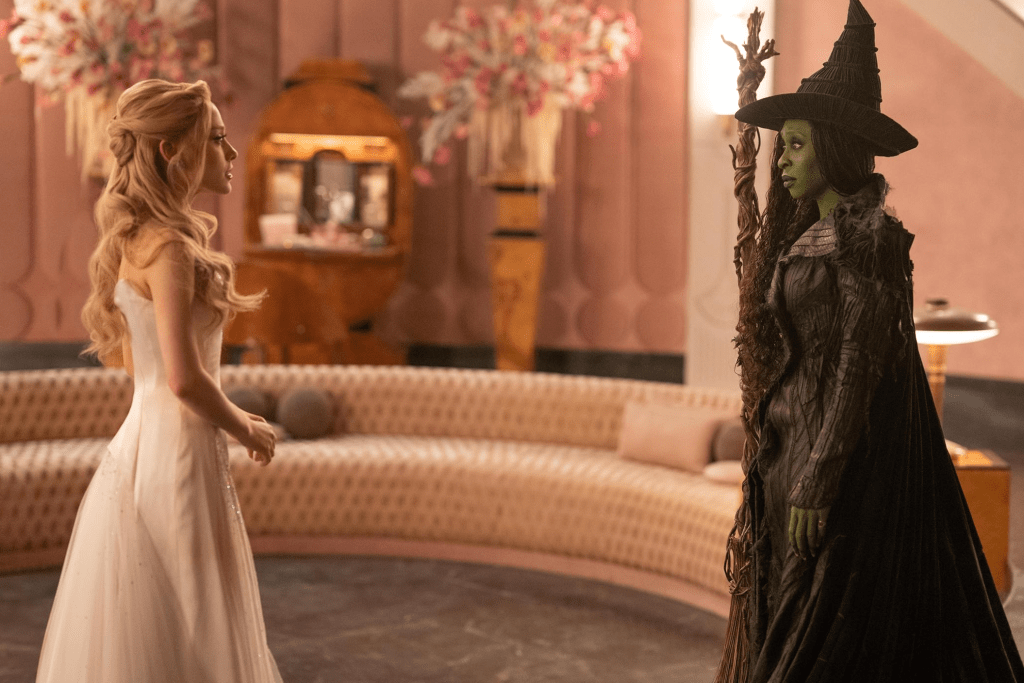

Don’t get me wrong—there are elements of For Good that work beautifully. The reunion between Elphaba and Glinda, where they finally hash out everything that’s gone unsaid, is gutting. Grande and Erivo play it with such raw emotion despite my frustrations with where the story goes. Their duet on “For Good” is lovely, though I found myself wishing it had more bite, more acknowledgment of the real harm that’s been done.

Erivo continues to be exceptional. Her performance of “No Good Deed,” where Elphaba grapples with the consequences of trying to help the people she loves, is a powerhouse showcase that demonstrates why she’s one of the best vocalists working today. The pain and rage and guilt Erivo brings to this number is shattering. And the quiet moments—Elphaba tending to Animals, Elphaba reading the Grimmerie, Elphaba’s face when she realizes she has to let Glinda go—are all beautifully played.

The film does make one change I genuinely appreciated: Dr. Dillamond gets his voice back. In the stage musical, we never learn what happens to him, but the implication is grim. Here, in the film’s final montage, we see him restored to his position at Shiz, speaking again. It’s a small grace note, but it matters. It suggests that some wounds can be healed, that some of what was lost can be reclaimed.

But that moment of restoration makes Glinda’s inaction throughout the rest of the film even more glaring. She has the power, the platform, and eventually the magic to fight back, and she doesn’t. Not until it’s over. Not until the cost has been paid by everyone else.

Jonathan Bailey’s Fiyero gets more to do in this film, and he’s wonderful—torn between his feelings for both women, trying to do the right thing, ultimately choosing Elphaba and paying dearly for it. The transformation into the Scarecrow is handled with more pathos than I expected, and Bailey sells every moment of it. His Fiyero is proof that you can start as someone shallow and become someone brave without it feeling unearned.

The production values remain impeccable. The set pieces are stunning. The costumes continue to be works of art. The cinematography is lush and evocative. Technically, this is still a beautiful film. But beautiful technique in service of a muddled message is just expensive confusion.

I keep thinking about who this story is for and what it’s trying to say. The first film understood that sometimes doing the right thing means losing everything—your reputation, your relationships, your safety. It understood that standing up to injustice is costly and lonely and terrifying, and you do it anyway because some things are more important than being liked or safe or comfortable.

But the second film seems to argue that you don’t actually have to pay those costs if you’re pretty and popular and well-meaning enough. That you can wait until it’s convenient to take a stand. That being complicit in oppression is forgivable if you eventually do something good after everyone who actually fought has already sacrificed everything.

That feels like a dangerous message to send, especially to young people. Especially now.

Wicked: For Good wants to have it both ways. It wants to critique systems of oppression while also redeeming someone who upheld those systems. It wants to be a story about resistance and integrity while also celebrating someone who compromised both until it was safe not to. It wants to honor Elphaba’s courage while also making sure Glinda gets her happily-ever-after, complete with magic powers and public adoration and the moral high ground she didn’t earn.

And I’m left feeling like the story told me that the privileged person’s comfort and redemption arc is more important than the marginalized person’s pain and resistance. That Glinda’s journey toward being “good” is more narratively valuable than Elphaba’s unwavering commitment to doing good regardless of cost.

I wanted to love this movie. I wanted the conclusion to this story to be as powerful and moving as the first part. And there are moments—that door scene where they say goodbye, the “For Good” duet, Erivo’s performance throughout—that touched me deeply.

But I can’t shake the feeling that Wicked: For Good is ultimately a story about how the privileged get to learn and grow and be redeemed at their own pace, while those without that privilege have to fight and sacrifice and sometimes die to force that growth. And I’m not sure that’s a story worth celebrating, no matter how beautifully it’s told.

Cynthia Erivo deserves every accolade for her work across both films. Ariana Grande does powerful work here, even if I disagree fundamentally with where her character ends up. Jon M. Chu has crafted two visually stunning films that showcase his directorial talents.

But sometimes beautiful filmmaking in service of a compromised message just means you’ve made something pretty that doesn’t hold up under scrutiny. And Wicked: For Good, for all its moments of genuine emotion and technical excellence, ultimately tells a story about complicity and redemption that I can’t fully embrace.

Glinda isn’t redeemable to me. Not because she can’t be redeemed in theory, but because the film doesn’t actually make her earn it. She doesn’t suffer the consequences of her choices. She doesn’t lose anything she can’t get back. She doesn’t have to live in exile or die or sacrifice her safety or comfort in any lasting way. She gets to stay in Oz, beloved and powerful, with magic to boot, while Elphaba has to fake her death and abandon everything she ever knew just to survive.

And we’re supposed to think this is a happy ending for both of them?

I don’t buy it. I can’t buy it. Not when I’ve watched what Glinda chose at every turn. Not when I’ve seen what those choices cost everyone else.

Wicked: For Good is a well-made film with moments of genuine power and beauty. But it’s also a film that fundamentally misunderstands what made its source material resonate, that centers the wrong character’s journey, and that ultimately peddles a message about complicity and redemption that feels hollow at best and harmful at worst.

Your mileage may vary. Many people will love this movie, and I understand why—it’s emotional, it’s beautiful, and the performances are strong. But for me, this is a story that chose the easy path when it should have stayed difficult. That gave us comfort when it should have challenged us. That made Glinda good instead of making her reckon with what it really costs to become good after you’ve been complicit in evil.

And that’s not defying gravity.

Leave a comment